Lost Jewish Worlds |

|||||

|

Home | |

Grodno to WWI | |

Between the Wars . . . 1. Demographic Changes 2. Antisemitism & Pogroms 3. Education & Religion 4. Cultural Life 5. Political Activity |

| Under Soviet Rule | |

German Occupation . . . 1. Fall of the City 2. Deportations to the Ghetto 3. Confiscation & Forced Labor 4. Liquidation of the Ghetto 5. Underground Activities 6. After the War |

| Bibliography |

BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS - 5

Political and Zionist Activity. Grodno�s Jews were active in political life on both the national and municipal levels, within the framework of Jewish parties or on joint lists with other minorities. In the 1928 elections, 70 percent of the eligible Jews voted, as compared with 60 percent of the Poles.

The main activities, however, focused on intra-Jewish politics. Virtually all streams, viewpoints, parties, and movements were repre-sented in Jewish Grodno. Political activity was at its most intense during the campaigns for the Sejm and the Senate or, at the local level, for the municipality and the Va�ad ha-Kehillah. The influence of the Jewish parties and movements went beyond politics or ideology. They formed lists to run in elections, established educational institutions, published journals, and served as social centers.

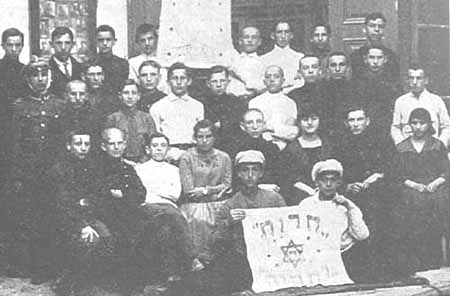

The first regional conference of the Jewish State Party, Grodno 1934

The Zionists maintained lively activity in the city. Nearly every week groups of settlers left for Eretz Israel, among them not only halutzim, but also merchants and artisans from the middle class, individuals as well as entire families. It is estimated that, by 1935, between 4,000 and 5,000 Grodno residents had settled in Eretz Israel.

The Zionist movement had a building of its own, which housed the various factions and organizations: General Zionists, the Hitahdut and Poalei Zion-ZS, the youth movements, organizations like WIZO, the national funds (Keren Hayesod and the Jewish National Fund), the Eretz Israel Office, which dealt with aliyah, the Brenner Library, and others. Besides ongoing activity the center was also the arena of the election campaigns for the Zionist institutions and maintained contact with the surrounding towns of Jeziory, Ostryn, Amdur, Lunna, Nowy Dwor, Suchowola, Sokolka, Skidel, and Porzecze. At the time of the 1928 elections, there were 12,000 Zionist activists and sympathizers in Grodno and the region.

In 1921, a year after Poalei Zion split into �left� and �right� wings, the movement�s young members in Grodno chose to affiliate themselves with the Zionist-socialist right-wing. In 1925, Poalei Zion merged with ZS (Zionist-Socialists), and the united organization became the majority faction in Grodno. Most of its members were salaried workers and clerks, although there were also those in the liberal professions, and teachers, artisans, and small shopkeepers. ZS also brought with them to the Zionist House the Brenner Library, with its thousands of volumes in Yiddish and Hebrew on the Jewish labor movement and on socialist Zionism. The library also attracted many readers who were not organized in youth movements but became the nucleus of the Freiheit (�Freedom�) movement.

Betar leaders, Grodno 1935 (front row center, M. Begin)

Members of Betar, Grodno 1932

Conference of Heruth u-Tehiyah in Grodno. Last row, third from left, Josef Zandman

Members of the Akivah movement

Another prominent group in Grodno and the area, particularly among the Jewish intelligentsia, was the Hitahdut (Socialist-Zionist Labor Party). In the 1920s, this faction did much to strengthen the He-Halutz organization and promote aliyah. The Hitahdut advocated the revival of the Hebrew language and was among the initiators and supporters of the Tarbut school system. In 1928 it had about 2,800 members and supporters in the city.

The national-religious Ha-Mizrachi faction was established after World War I. In Grodno its members were among the veterans of the Zionist camp. In 1921, all fourteen of its candidates were elected to the Community Council, and for years it was the third largest party in Grodno in terms of the number of electors to the Zionist Congresses. The movement�s Grodno branch also had various affiliates: Ze�irei Ha-Mizrachi (�Young Mizrachi�), Torah va-Avodah (�Torah and Labor�), Ha-Shomer ha-Dati (�Religious Guardian�), and He-Halutz Ha-Mizrachi. In 1935 a branch of the Center for Religious Artisans was founded in the city.

The Revisionist Movement was established following Ze�ev Jabotinsky�s resignation from the Zionist Executive in 1923. The new organization soon acquired an influential status in Grodno, and Jabotinsky was enthusiastically welcomed when he visited the city. The movement�s chairman, Dr. Blumstein, also served as the head of the Kehillah. In addition to the Revisionists� youth movement, Betar, a paramilitary group called the Brit ha-Hayal (�Soldier�s Alliance�) was active. Its members were mainly ordinary working-class folk � porters, wagoners, butchers, etc. � who were ready to fight for their people, as they exhibited during the 1935 pogrom.

The non-Zionist camp included the Bund, the first and largest Jewish socialist party, founded in 1897 in tsarist Russia. However, in inter-war Poland its influence was initially quite limited. The turning point, which transformed the Bund into a mass party in Poland, occurred in 1936. Then the Jews� economic and security situation deteriorated, while the immigration quotas to Palestine were slashed, and the United States and other countries blocked immigration altogether.

In Grodno the Bund gained a majority already in 1928, in the elections to the Va�ad ha-Kehillah, and it had the allegiance of 3,000 members and supporters. Its main strength came from the Jewish workers in the city�s veteran tanning industry, but it also drew support from many intellectuals as well as from workers and artisans.

The Communist Party was outlawed in Poland and thus operated underground, but this did not deter many Jews from joining it, in the belief that a communist regime would solve the Jewish problem. The surging antisemitism in Poland in the 1930s only strengthened the communists and attracted to them respected members of the community, such as the lawyer Gozhansky.

The ultra-Orthodox element in the non-Zionist camp was represented first and foremost by Agudat Israel. In 1918 Agudat Israel was still an umbrella organization for many Grodno haredim who did not belong to any party, including those who rejected the Zionist shekel (a tax paid on the eve of each Zionist Congress). It was not until a few years later that the Grodno faction organized itself as a party subordinate to the center in Warsaw. Its strength lay in the influence it exerted over the community�s religious institutions, such as houses of worship, hadarim and yeshivot. In 1934, the party established its own educational system in Grodno, comprising a kindergarten, the Beth Ya�acov girls� school, and later also a college for ultra-Orthodox teachers. A police report describes the members of Agudat Shlomei Israel (some 3,000 in number) as being loyal to the government (indeed, they believed in the ancient dictum, �Dina de-malkhuta Dina� � the law of the land is binding � and often voted for the ruling party).

Group of Ha-Shomer ha Zair, Grodno 1932

Ha-Shomer ha-Zair members from Grodno celebrating Lag Ba'omer

Members and friends of He-Halutz vishiting a hakhshara group on a farm

The strongest youth movements in Grodno were Dror, Ha-Shomer ha-Za�ir, and Betar (Revisionists). Dror was founded in 1926, as a union of He-Halutz ha-Za�ir and Freiheit, the movements of Poalei Zion and ZS. At the end of 1927, the Dror branch in Grodno was one of the largest in Poland, numbering some 200 members from all walks of life. The major ideological difference between the two movements lay in their choice of language: He-Halutz ha-Za�ir preferred Hebrew, while Freiheit opted to cultivate Yiddish culture among its young members. The movement ran eleven amateur groups, including a drama group, a string orchestra, and the Ha-Koah sports association. The emphasis was on what they called �Eretz Israel work� and aliyah, including work for the national funds. The young people also took part in trade-union activity and in demonstrations of a socialist character and maintained contacts with branches of the movement in Jeziory, Amdur, Sopockin, Sokolka, Skidel, and Krinki.

Ha-Shomer ha-Za�ir, a left-wing, pioneering-scouting movement, inaugurated its activity in Grodno in 1923/24 with a boys� group called Ahdut and a girls� group called Kadimah. Their activity quickly spread outside the city as well. Young people from all the surrounding towns joined, and the movement leadership in Grodno organized local branches for them. Very soon a Grodno district center was established, which cooperated with the Vilna and Bialystok districts. Among other programs, the Grodno district organized summer camps for youth from the entire region. Every year Ha-Shomer groups and their leaders went to local villages where they rented peasants� homes and devoted their time to ideological studies, sports, scouting, and cultivating Hebrew song. In 1926, a co-ed group called Karit inaugurated a permanent hakhsharah program at Czenstochowa and Siemiatycze. Although the group later disbanded, as many of its members settled in Eretz Israel (among them founders of Kibbutz Ein ha-Horesh) and others pursued their education, it enshrined the idea of hakhsharah (agricultural training) and aliyah. A younger group, called Shomriyah (whose members helped found Kibbutz Ein Shemer), were leaders in the local branch. Its members attended a hakhsharah program near Sokolka, then the central training farm at Czenstochowa, and from there proceeded to Eretz Israel. There was also the Massada group, whose members were active in the Grodno district leadership (one of them, Mattityahu Shor, was a founder of Kibbutz Ein ha-Mifratz). Between 1935 and 1939, the Grodno branch numbered about 500 young people aged twelve to twenty, pupils of Tarbut and working youth. Educational activity was an important part of movement activity, with those aged sixteen to seventeen serving as group leaders for the thirteen and fourteen-year-olds.

Most of the members of the He-Halutz Organization of the Eretz Israel ha-Ovedet League were graduates of Ha-Shomer ha-Za�ir and Dror. The emphasis here was on Zionist-socialist education and on practical training for aliyah, together with work on behalf of the Zionist funds, distribution of shekalim for the Zionist Congresses, and activity in the Tarbut schools.

Betar focused on military education, although it did not scorn pioneering settlement (maintaining several work and training groups). Many of the movement�s members reached Eretz Israel in a variety of ways, only a few by means of immigration certificates which they obtained as students or as professionals. They often immigrated illegally on the rickety ships of �Aliyah Bet� (illegal immigration to Palestine). Besides the three large youth movements, smaller groups such as Akivah (General Zionists), which in the 1930s had some 150 members, most from the Polish high school and Tarbut counterpart, could be found in Grodno. The movement was divided into �battalions,� and its center was the Beit Ha�am (�People�s House�) building. There was also the non-Zionist Zukunft (�Future�) movement run by the Bund, but, unlike the parent organization, it had little impact in Grodno.

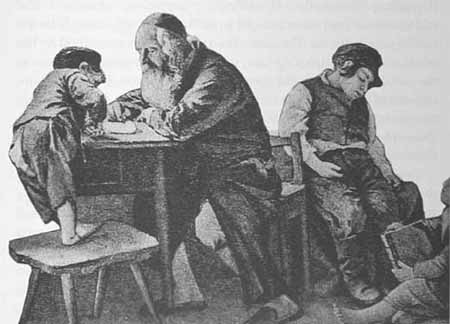

A heder in Grodno

Home