Lost Jewish Worlds |

|||||

|

Home | |

Grodno to WWI | |

Between the Wars . . . 1. Demographic Changes 2. Antisemitism & Pogroms 3. Education & Religion 4. Cultural Life 5. Political Activity |

| Under Soviet Rule | |

German Occupation . . . 1. Fall of the City 2. Deportations to the Ghetto 3. Confiscation & Forced Labor 4. Liquidation of the Ghetto 5. Underground Activities 6. After the War |

| Bibliography |

GRODNO

Known to the Jews as Horodno or Grodne.

Before World War II a County Seat in the Bialystok

District.

Tikva Fatal-Kna’ani

Grodno before World War II, general view and the Nieman river

The Grodno district is located in northwest Byelorussia, bordering on the north with Lithuania and on the west with Poland. The population was largely Byelorussian, Lithuanian, and Polish. Four rivers – the Bug, Narew, Nieman, and Bover – run through the district; there are a number of lakes in the north and east. The agricultural produce of the area consisted of rye, wheat, linen, tobacco, fruits and vegetables. Industrial products have been diverse, including textiles, pelts, wool, bricks, and alcoholic spirits.

Between the two world wars Grodno served as the county seat in the district of Bialystok. It is located on the high right bank of the Nieman River, near the Polish border, and is situated at an important railroad junction on the main road from Warsaw to St. Petersburg. It was a commercial center for grains and the site of a variety of industries: large spinning mills, tanneries, and factories producing tobacco and cigarettes, shoes, glass, paper, soap, and agricultural machinery.

Although Grodno was already inhabited during the first millennium C.E., it is not mentioned in historical documents until the year 1128, when it appears as the seat of its first prince, Vsevolod Davidovich. In 1224, it was destroyed by German knights, and in 1241, during the reign of its fifth and last prince, Yuri Glebovich, by the Tatars. Immediately afterward it was captured by the Lithuanians. In the early fourteenth century Grodno was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1444 it was granted city status (Magdeburg city rights).

Grodno was devastated in 1284, and again in 1391, in the wars between Lithuania and the Teutonic Order (from eastern Prussia). In 1398, Prince Vitold of Lithuania made Grodno his second capital, after Vilna. The king and his entourage occasionally stayed in Grodno, and after the union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the “Union of Lublin,” 1569) the Polish Sejm (national assembly) met there. King Stefan Batory of Poland resided in Grodno, where he died in 1586.

During the period of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Grodno was an important Catholic center, and impressive church edifices from that period still exist there. From 1655 to 1657 the Russians, who were at war with Poland, occupied Grodno; they were followed by the Swedes. Charles XII encamped there from 1705 to 1708, on the eve of his invasion of Russia. Important sessions of the Polish Sejm were held in Grodno: the “Silent Sejm” (1793), which was forced to approve the second partition of the country; and the Sejm of 1795, prior to the third partition, after which Grodno was annexed to the Russian Empire. In 1801, Grodno became the main city of a Russian province.

On the eve of World War I, Grodno’s defenses were reinforced, and it was incorporated into the second line of fortifications in western Russia, but in September 1915 it fell to the Germans without resistance. In 1918, Grodno was returned to Poland and included in the Bialystok district. With the partition of Poland between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in September 1939, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Grodno was annexed to the Byelorussian Soviet Republic. Grodno was one of the first Soviet cities captured by the Germans in 1941. In June 1944, it was retaken by the Red Army. Today, as the twentieth century draws to a close, Grodno is a city in the state of Byelarus.

GRODNO JEWRY

Grodno was one of the oldest Jewish communities in Greater Lithuania. It appears that Jews already resided there at the end of the twelfth century – refugees from the Kingdom of Kiev and from western Europe who fled from the Crusades – but this cannot be confirmed. The first reliable evidence of a Jewish community at the site is a charter of “privileges” (a settlement permit specifying rights and obligations) from 1389, granted to the Jews by Grand Duke Vitold of Lithuania. The document suggests that the Grodno Jews had already established a synagogue and a cemetery and also owned real estate in and around the town; they made a living from commerce, crafts, agriculture, and leasing land. The charter, which was intended primarily to regularize the Jews’ rights vis-a-vis the Christian townspeople, permitted their use ` of public grazing fields, forests, and meadows. The synagogue and cemetery were exempted from all taxation.POPULATION

| Year | Number of residents | Number of Jews | Percentage |

| 1560 | - | about 1000* | |

| 1776 | - | 2,418 | |

| 1816 | 9,873 | 8,422 | 85.3 |

| 1859 | 19,920 | 10,300 | 51.7 |

| 1887 | 39,826 | 27,343 | 68.7 |

| 1897 | 46,919 | 22,684 | 48.3 |

| 1906 | 41,607 | 25,191 | 60.5 |

| 1921 | 34,694 | 18,697 | 53.9 |

| 1931 | 49,699 | 21,159 | 42.6 |

| *Estimate based on census of houses | |||

From the Sixteenth Century Until the End Of World War I

The Status and Conditions of the Jews. In 1495, all the Jews, including the Grodno community, were expelled from Lithuania. Their property was confiscated and, in part, turned over to the Christian population. Eight years later Prince Alexander permitted the Jews to return and to reclaim their property. This was stated explicitly in a decree given by the prince to two Grodno Jews, Eliezer Ben-Moshe and Yitzhak Ben-Faibush. However, negotiations between the Jews and Christians on the return of the property dragged on for years, until King Sigismund I of Poland intervened on behalf of the Jews in 1526. In 1540, Queen Bona reaffirmed the right of Grodno’s Jews to their real estate, but ordered them to pay 17 percent of the taxes levied on Grodno by the duchy.

Lithuania’s Jews suffered badly during the military campaign conducted by the Russian tsar (1655-1657). Although the tsar rejected the demand of the city dwellers to expel the Jews, he imposed severe restrictions that seriously affected their livelihood. In 1633, King Ladislaus of Poland forbade the Jews to purchase new houses or to enlarge the existing ones on the pretext that the Jews were overrunning the city and causing harm to the Christians. In 1667, when the Polish Sejm began to meet at Grodno, King Sobieski further reduced the areas of Jewish residence, claiming that because of the Jews there were insufficient rooms for the delegates to the Sejm. However, King Mikhael Vishnovietzki (who reigned from 1669 to 1673) granted the Jews a privilege that reaffirmed all their former rights.

Grodno’s Jews were not harmed during the calamitous events of 1648. They were even able to serve as a haven to refugees who fled from Chmielnicki’s forces and to extend financial assistance to their brethren in other communities.

From 1616, the city’s Jews suffered from persecutions at the hands of Christian zealots (the Jesuits), who kidnapped Jewish children and baptized them as Christians. The Jews were forced to raise funds to meet the high ransom payments demanded for the children.

In the eighteenth century the wars with the Swedes (1705) brought destruction and devastation, and many fell victim to an outbreak of plague in 1740. The Jews were also heavily burdened by debts, often falling behind in their payments. Moreover, Christians who owed money to Jews used various ruses to avoid paying their debts; many were aided by government officials in their evasive tactics, as is indicated by the Jewish community’s complaint to the king’s aides. Yet some Jews had protectors among the nobility and turned to them for support in this matter.

Shortly before and for some years after the partition of Poland (1793), Grodno’s Jews became the target of blood libels. In 1790, Eliezer Ben-Shlomo was accused of having committed ritual murder and was executed, despite the king’s objections. The same pattern was repeated in 1816 and in 1820, but on these occasions the imprisoned Jews were released thanks to the intercession of the central government. In 1906, following a pogrom against the Jews of nearby Bialystok, a wave of refugees streamed into Grodno, where they found relief and shelter. The pogrom, together with the antisemitic mood that prevailed in the region from 1903 to 1907, spurred Grodno’s Jews to take measures of self-defense.

Economic Life. The traditional occupations of Grodno’s Jews were various branches of commerce (mainly agricultural produce and timber) and crafts. Beginning in the late nineteenth century they also ventured into industry.

In the sixteenth century local Jews made their living from export, mainly of grains and other agricultural produce, to large cities in Poland and Lithuania, but their goods also reached Koenigsberg, Danzig, and Posen. When they returned from their business trips to such places they imported into to Grodno iron and steel products, spices, rice, silk and cloths, as well as other goods. The most important of these exporters, Yehuda Bogdanovich, bore the title “Merchant of Queen Bona,” and his family was famed for its wealth and influence among both Jews and non-Jews throughout the Grodno region. His descendants were known among Jews as “Yehudichis.” Other Grodno Jews also owned farm lands and estates, but their number declined following the Union of Lublin in 1569: after that date they could no longer compete on equal terms with the nobility, who were granted preferential status, like their Polish counterparts.

The Jewish merchants in Grodno flourished and frequently took part in fairs outside the city, even in the famous fair of far-away Leipzig. Their economic success spurred the growth of the city’s Jewish population in that it induced Jews from nearby towns to move to Grodno. The city was ringed with Jewish settlements in nearby locales, such as Novogrodek, Tiktin, Nowi-Dwor, and others.

In 1601, King Sigismund III acceded to the request of the Christian townspeople and prohibited Jews from purchasing grains in villages or at fairs and from transporting them on the Nieman River. The farming out of taxes and tolls provided another solid source of income for Grodno’s Jews. Here, however, they had to compete with the Jews of Brest-Litovsk (Brisk), the largest and most important Jewish community in Lithuania, and, indeed, they often lost deals to the Brest-Litovsk merchants.

The many Jewish craftsmen encountered acute hostility from Christians, in particular from artisans’ associations, which stopped at nothing to interfere with the Jews and force them to join their societies. The Jews fought for their rights and, in 1629 and 1633, were granted a privilege permitting them to engage in crafts outside the framework of the associations. Later, in 1654, the Jewish craftsmen were forced to pay the associations a levy of five gulden and six funt of gunpowder for the city’s defense. In return, they received the right to benefit from the general privileges granted to non-Jewish artisans.

In the mid-nineteenth century the growing economic importance of Bialystok proved harmful to Grodno’s Jews, who for centuries had been the leading economic factors in the region. In 1859, Grodno merchants still constituted 15.8 percent of all the merchants in the province, but, by 1886, this had fallen to 12.3 percent. In no small degree this process was caused by a series of great fires that swept the city in the nineteenth century. On May 29, 1885, much of the city was consumed in a blaze that also gutted six synagogues and the Jewish orphanage. Rebuilding was undertaken with the aid of generous outside contributions, including 25,000 rubles from the Tsar and 5,000 from the Crown Prince. Another fire, in July 1900, laid waste the entire city, this time destroying twelve synagogues, some of them centuries old.

Nevertheless, the Jews remained a central factor in the city’s economy. In 1886, 65 percent of the real estate in Grodno was owned by Jews; Jews owned 1,165 businesses (88 percent of the total); 103 of the 129 registered merchants were Jews; 76 percent of the city’s industry was in Jewish hands; and Jews also accounted for 70 percent of the craftsmen, a constantly rising proportion. Most of these commercial enterprises were retail or small-scale businesses; the same applied to the crafts.

Portrait of Rabbi Nahumke (Nahum Ben Uziel)

Title-page of Rabbi Alexander Suesskind's Zava'ah

Excerpts from the statutes of the Chevrat Mishnayoth

Ve'Alshich in the "Across teh River" suburb, 1767

In 1897, there were 13,147 Jewish providers in Grodno:

| Clothing and textiles | 3,563 |

| Commerce and agricultural produce | 2,408 |

| Construction | 1,771 |

| Domestic service and day work | 1,320 |

| Timber products | 1,170 |

| Transportation | 1,148 |

| Manufacture of fabrics | 109 |

| Tobacco industry | 1,658 |

However, working conditions in the factories and the workshops were abominable, the hours were long, and the pay was poor. Emissaries from Bialystok and elsewhere tried to organize the workers to demand their rights, but to no success. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that salaried carpenters and tailors went on strike; as a result they were able to work fewer hours a day. A strike in Shershevski’s factory achieved higher wages for the workers there.

The Jews maintained their dominant place in the city’s economy until World War I, but later, when Grodno was returned to Polish rule, their fortunes declined. In 1921, Jews owned 1,273 industrial plants and workshops, which employed 3,719 workers (including 2,341 salaried workers, of whom 83 percent were Jews); of these, 34.6 percent were in the food industry, and 29 percent manufactured clothing. By 1937, Grodno’s Jews owned sixty-five large and medium-sized plants, employing 2,181 salaried workers (41 percent of them Jews), as compared with 51 government and non-Jewish plants, which employed 2,262 salaried workers. Forty-five percent of all those employed in Jewish-owned factories worked in the timber industry, but only 28 percent of them were Jews. The most important Jewish-owned concerns at the time were: a large bicycle factory, a factory for leather goods and artistic book-binding, a glass factory, a graphics and lithographic enterprise, and foundries and breweries. Some of these plants served as training sites for halutzim (pioneers) before they settled in Palestine. (In the 1920s the Polish authorities nationalized Shershevski’s tobacco factory and continued to operate it as a Polish state enterprise, see below.)

Community Life. A deeply rooted and flourishing Jewish community life existed in Grodno by the early sixteenth century. The community’s leaders handled general affairs and, because the seat of the supreme court (the Tribunal) of the Lithuanian duchy was located in Grodno, defended Jews in libel trials (blood libels or accusations of “desecrating the host”).

By the end of the century, a number of batei midrash and yeshivot had been established, and Horodno was written by the Jews as though it were Har Adonai (“The Mountain of the Lord”). Grodno also served as the Jewish spiritual center for the entire region. Eminent rabbis and Torah sages resided there, and the city boasted a famous yeshivah. In 1788, the Royal Press in Grodno printed the first Hebrew book to be published in Lithuania. Five years later a second Hebrew press began operating in the city; this would evolve into the famous “Printing Press of the Widow and the Brothers Romm,” which later relocated to Vilna.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the peak period of Lithuanian Jewry’s internal autonomy, the Grodno community achieved primacy. The Council of Lithuanian Jewry (“Va’ad Medinat Lita”), which was founded in the early sixteenth century and existed until 1764, usually met in Grodno or in towns in the Grodno region – Miesteczki, Zabludow, Krynki, and Amdur. The Council consisted of heads of the Kehillah and the rabbis of the three major communities – Brest-Litovsk (Brisk), Grodno and Pinsk (according to their order of importance), and later also Vilna and Sluck. They also represented the local communities that were under their authority. Seven communities were under the authority of Grodno: Nowi-Dwor, Amdur, Miesteczki, Kuznica, Ostryna, Radun and Lida, together with their subsidiary communities (“surrounding settlements”).

The Grodno community elders not only represented them in the Communities’ Council assemblies, they also determined their share of the royal taxes, collected them, and raised funds for special purposes (such as bribing government officials, and the like). The Grodno rabbi supervised the rabbis of the other communities and was their supreme arbiter; the rabbis of the three principal communities were signatories to the Council’s constitution. The Grodno community’s senior status was further reflected in the division of the various tasks and duties. For example, the community undertook, under the regulations of the Council, to arrange the marriage of ten needy girls every year (out of thirty girls whose marriages were arranged by the Council). In 1639, during the Thirty Years’ War, when destitute Jewish boys arrived in Lithuania from Western Europe, the Council of Lithuania made the Grodno community responsible for the upkeep and education of ten of the fifty-seven boys.

When a dispute broke out between the Grodno and Keidaniai communities over the supervision of a few small communities on the banks of the Nieman River, the Council ruled, in 1662, that they would be answerable to Grodno. In 1776, the Grodno Jewish community of 2,418 constituted the majority in the town.

Title-page of Nezer Aharon by Rabbi Miadler

Title-page of the records of the "Shas Chevrah"

in the "Across the River" suburb, 1830

Rabbi Mordecai Diskin, one of first

Grodno Jews who Settled in Petah-Tikvah

Letter of the "Yishuv Eretz-Israel" society in Grodno

concerning the purchase of land in Petah-Tikvah, 1880

Michael Uriahson, delegate to the 1st Zionist Congress

In 1617, a large fire devastated the entire Jewish quarter. Two years later, King Sigismund III granted three Jews permission to rebuild their homes. Instead of the wood synagogue, which was destroyed in the blaze, a new brick synagogue was erected. (This may have been the “great” synagogue known as Ha-Levush, because, according to local tradition, its founder was Rabbi Mordecai Yoffe, author of Levush Malkhut, a ten-volume codification of religious laws that particularly stressed the customs of the the Jews of Eastern Europe.) In the eighteenth century a second large Jewish community took shape, the Ferstot (“Across-the-River” quarter); already in 1723 there was a report of regular services being held in a large synagogue in that suburb.

Another fire, in 1899, again levelled the Jewish quarter, including the Shulhoif (the synagogue courtyard-compound). Several hundred homes and fifteen houses of worship, including Ha-Levush, were destroyed.

Grodno Rabbis. Grodno was famed for its scholars and for the high reputation of its rabbis, who headed the yeshivah and served as signatories for the statutes of the Council of Lithuanian Jewry. In the sixteenth century the community’s spiritual leader was Rabbi Natan ben Shimshon Shapira Ashkenazi, a great scholar of Hebrew and Hebrew grammar, and the author, among other works, of Mevo She’arim and Imrei Shefer. He was succeeded, in 1572, by Rabbi Mordecai ben Avraham Yoffe, known by the title of his major work as “Ha-Levush” (b. Prague, 1530; d. Posen, 1612).

Although Rabbi Yoffe was a towering religious figure, his appointment generated a sharp controversy within the community because he was a relative of the “Yehudichis.” In 1549, opponents of the appointment took their complaint to Queen Bona. She summoned both sides to a hearing, but because only one party appeared she transferred the arbitration of the dispute to rabbis from other communities. In the wake of this case, the queen decided to formalize the election of rabbis and regulate their rights and obligations. A few years later, in 1553, she also formalized the status of the heads of the communities and stipulated procedures for appealing their decisions to the rabbis.

In time, Rabbi Yoffe came to be revered for his incisive wisdom. In addition to his religious occupations, he tended devotedly to the public’s needs, finding the time to attend the fairs at Yaroslav and Lublin, where community leaders and rabbis from large communities met to discuss matters of general interest. These meetings were the forerunners of the Council of the Four Lands and the Council of Lithuania.

The Grodno chief rabbi usually also served as the president of the rabbinical court and head of the yeshivah. Rabbi Yoffe was succeeded by Rabbi Yuda, who was followed by Rabbi Ephraim Zalman ben Naftali Hirsch Shor, author of Tevuot Shor and afterward the rabbi of Brest-Litovsk (d. 1634). A number of well-known rabbis served in Grodno in the first half of the seventeenth century: Rabbi Avraham ben Meir Halevi Epstein (from 1616 to 1644); Rabbi Yehoshua Heshil ben Yosef Harif (b. Vilna, c. 1580; d. Cracow, 1648), author of Meginei Shlomo and Pnei Yehoshua; and, alongside him and for a time afterward, Rabbi Yitzhak-Isaac ben Avraham Katz (d. 1643 in Grodno).

Grodno’s spiritual leaders after the Chmielnicki pogroms of 1648 were Rabbi Yonah ben Yeshayahu Te’omim (b. 1596, Prague; d. 1669, Metz), author of Kikayon de’Yonah; Rabbi Moshe, the son of Rabbi Natan Shapira of Grodno (d. 1665); Rabbi Yitzhak ben Avraham (“Rabbi Yitzhak the Great”), who owned a vast collection of books and ancient manuscripts; and Rabbi Mordecai Sueskind ben Moshe of Rothenburg (Hesse, Germany), one of the most renowned rabbis of his generation and author of a work of Responsa, who served from 1681 to 1683. The last to bear the title of Rabbi of Grodno was Rabbi Binyamin Braude (d. 1818). The dispute over the rabbinate following Rabbi Braude’s death led to its abolition in Grodno and the appointment of dayanim (religious judges). Religious authorities who resided in Grodno included the kabbalist and moralist Rabbi Alexander Suesskind, author of Yesod ve-Shoresh ha-Avodah and Zava’ah. Another whose name was known far and wide in the nineteenth century as a great scholar was Rabbi Nahum ben Uziel – “Rabbi Nahumke” – but his modesty kept him from assuming office. He devoted himself to raising funds and caring for the poor.

A personality whose religious and spiritual influence during the nineteenth century was remarkable – not only in the Grodno region but in all Poland and Lithuania – was Rabbi Moses Isaac Darshan, known as the Kelmer Maggid (1828-1899); he was the main preacher of the Musar (“Ethics”) Movement (see the chapter on Lida).

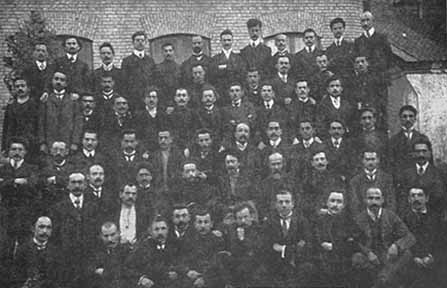

The Poalei-Zion commitee in Grodno, 1904-1908

Farewell party fot Leib Jaffe prior to his aliyah

The first class of the Hebrew Pedagogical Courses

The poet Shaul Tchernichovsky on a visit to the Hebrew Pedagogical Courses, 1909

Education, Culture, Enlightenment. Nineteenth-century Grodno had many batei midrash (religious schools) and study societies in the style of the Mitnaggedim (opponents of Hasidism), in which Jews from all walks of life studied Torah, and not only on the Sabbath. From about mid-century greater emphasis was placed on educating the community’s children. In 1849, a state elementary school was opened, followed by a girls’ school and a vocational school. At the same time, a Talmud Torah (religious elementary school) continued to operate (it had 240 pupils in 1879), as did the yeshivah (about 120 students). In 1886, there were forty-nine Jewish elementary schools and hadarim (religious schools for small children) in Grodno, which were attended by 869 of the city’s 1,100 Jewish pupils. In 1900, a heder metukan (reformed heder) was founded under the auspices of the Zionists; it operated until Grodno’s occupation by the Germans in 1915. The language of study was Hebrew and the curriculum was infused with the ideals of the Jewish national movement. Within a few years Arye Leib Miller established a second modern heder, called “Yeshurun,” in which Hebrew, including grammar, and Jewish history were taught. By 1906, there were 106 boys’ schools in Grodno, with 1,766 pupils (including about 100 hadarim attended by 1,200 boys).

In 1897, there were 5,611 Jews who had acquired a general education in Russian, and another 4,411 whose general education was grounded in other languages.

Pedagogical courses for Jewish teachers, sponsored by the “Society for the Dissemination of Education,” gained fame throughout Russia and served as models for teachers’ training in many locales. Hundreds of pioneers of Hebrew education prepared themselves for their future work in Grodno’s courses, as did well-known writers and poets (Ya’akov Fichman, Ya’akov Lerner, Dr. Yisrael Rubin-Rivkai, and many others). Since 1907, the courses were held in a building erected especially for the purpose; it also housed an athletic association and a library. The pedagogical courses continued until World War I.

Two renowned authors who lived in Grodno were the Hebrew writer A.S. Friedberg and the Yiddish poet Leib Naidus.

Relief and Welfare. Jewish Grodno was rich in mutual-aid and welfare institutions, as the city’s affluent Jews competed with one another to establish orphanages, hospitals, old-age homes, and vocational schools. In 1899, a cooperative savings and loan fund was founded in Grodno, one of the first of its kind in Russia. Jewish welfare and relief organizations included “Linat Zedek” (care for the sick), “Somekh Noflim” (run by the community’s women), a clinic, a hospice for the poor, and a fund that gave interest-free loans with the backing of the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA).

Zionist and Socialist Activity. Zionism and the Hibbat Zion (“Love of Zion”) movement had deep roots in Grodno, dating back to the community’s support for the “Old Yishuv” in Palestine. Court records from 1539 reveal that there was a Jewish couple from Grodno who planned to settle in Jerusalem and who raised funds for the Jewish community in the Holy Land. Reb Fischel Lapin, a community activist in Jerusalem, arrived in that city from Grodno in 1863. Overall, in the late nineteenth century, Grodno’s Jews were among the first to respond to the call for national renewal. In 1872 and in 1880, societies for settling Palestine were established in the city, and a branch of Hibbat Zion was founded in 1890. Grodno was one of the most active centers of Zionist activity in all of Russia. The leaders of the local Zionist movement were the brothers Bezalel and Leib Yaffe. Zionist “shekels” (whose sale determined the number of delegates to the conventions of the Zionist Congress) were printed clandestinely in Grodno. In the first decade of the twentieth century, a number of Zionist associations, including Poalei Zion (“Workers of Zion”), were founded in the city. At the same time, Grodno Jewry was receptive to social movements and ideas. As early as 1875/6, a Jewish socialist circle was established in Grodno. In the 1890s, Jewish labor movements, led by the Bund, conducted political and trade-union activity among the workers of the tobacco factory.

Grodno During World War I.

On September 2, 1915, the Germans captured Grodno and occupied the city for three years. The war put an abrupt end to the city’s economic boom, and Jews and non-Jews alike were plunged into a crisis situation. Nevertheless, the Jews continued to maintain lively cultural activity. Yiddish especially enjoyed a revival: Yiddish-language schools and a Yiddish theater were established, and many cultural activities were conducted in that language.

Home